Brugada Syndrome

Brugada syndrome refers to a hereditary disease that is associated with a risk of sudden cardiac death. It is characterized by typical ECG abnormalities: ST segment elevation in the precordial leads (V1 - V3).

The Brugada brothers were the first to describe the characteristic ECG findings and link them to sudden death. Before that, the characteristic ECG findings, were often mistaken for a right ventricle myocardial infarction and already in 1953, a publication mentions that the ECG findings were not associated with ischemia as people often expected.

General features

- The diagnosis is based on ECG findings.

- It is an inheritable cardiac arrhythmia syndrome with an autosomal dominant inheritance.

- Males are often more symptomatic than females, probably by the influence of sex hormones on cardiac arrhythmias and/or ion channels.

- The arrhythmias typically occur in patients between 30-40 years of age and often during rest or while sleeping.

- The right ventricle is most affected in Brugada syndrome, and particularly (but not specifically) the right ventricular outflow tract.

- The prevalence varies between 5-50:10.000, largely depending on the geographic location (especially in some Southeast Asian countries the disease is more prevalent).

Clinical diagnosis

The clinical diagnosis of Brugada syndrome is confirmed in an individual with the following:

| Findings | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECG | OMIM | Gene | Protein | Functional role in cardiomyocytes | Effect of mutation | |

| And at least one of the following | ||||||

| And at least one of the following | OMIM: Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man compendium of human genes and genetic phenotypes; BrS1–BrS7: Brugada syndrome types 1–7; NC: no consensus; ICa,L: L-type calcium current; If: hyperpolarization-activated current; IK,ATP: ATP-sensitive potassium current; INa: fast sodium current; Ito: transient outward potassium current. | |||||

Physical examination

Patients can present with symptoms of arrhythmias:

- Out-of-hospital-cardiac-arrest

- Syncope, pre-syncope (weakness, lightheadedness, dizziness)

- Chest pain

- Shortness of breath

- Paleness

- Sweating

Other clinical presentations of Brugada syndrome may include sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and sudden unexpected nocturnal death syndrome (SUDS), which is seen in southeast Asia in which young persons die from cardiac arrest with no identifiable cause (also known as bangungut in the Philippines, lai tai in Thailand, pokkuri in Japan and dab tsog in Laos.

However, most patients with Brugada syndrome are asymptomatic and are under medical attention because of family screening for sudden cardiac death/Brugada syndrome or because a Brugada ECG was found coincidentally.

Diagnosis and treatment

- Patients who are symptomatic (unexplained syncopes, ventricular tachycardias or aborted sudden cardiac death) may have a symptom recurrence risk of 2 to 10% per year. In these patients an ICD implant is advisable. Further, life-style advice is given (see below).

- Some groups advise an electrophysiological investigation (inducibility of ventricular fibrillation) for risk assessment in Brugada patients,[2][3] but others could not reproduce the predictive value of these tests,[4][5] so the value of inducibility is controversial.

- In large studies familial sudden death did not appear to be a risk factor for sudden death in siblings.

- In asymptomatic patients in whom the Brugada ECG characteristics are present (either spontaneously or provoked by fever or sodium channel blockers like ajmaline, procainimde or flecainide) life style advice is given. This advice includes:

- A number of medications should not be taken (including sodium channel blockers and certain anti-depressants and anti-arrhythmics, see www.BrugadaDrugs.org)

- Rigorous treatment of fever with paracetamol/Tylenol, as fever may elicit a Brugada ECG and arrhythmias in some patients.

- Spontaneous Type I ECGs do appear to be more prevalent in patients who experienced symptoms.

For a full list of the diagnostic criteria, see [6]

Electrocardiographic criteria

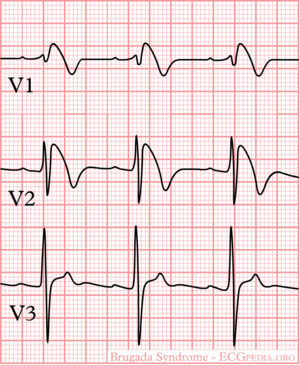

Three ECG repolarization patterns in the right precordial leads are recognized in the diagnosis of Brugada syndrome.

Type I is the only ECG criterion that is diagnostic of Brugada syndrome. The type I ECG is characterized by a J elevation >=2 mm (0.2 mV) a coved type ST segment followed by a negative T wave (see figure). Brugada syndrome is definitively diagnosed when a type 1 ST-segment is observed in >1 right precordial lead (V1 to V3) in the presence or absence of a sodium channel–blocking agent, and in conjunction with one of the following:

- documented ventricular fibrillation (VF)

- polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT)

- a family history of sudden cardiac death at <45 years old

- coved-type ECGs in family members

- inducibility of VT with programmed electrical stimulation

- syncope

- nocturnal agonal respiration.

The sensitivity of the ECG for Brugada syndrome can be increased with placement of ECG leads in the intercostal space above V1 and V2 (V1ic3 and V2ic3)

Electrocardiograms of Brugada patients can change over time from type I to type II and/or normal ECGs and back. A type III ECG is rather common and is considered a normal variant, but also the Type II is a normal variant (albeit suggestive of Brugada syndrome).

A recent study suggests that fractionation of the QRS complex is a marker of a worse prognosis in Brugada syndrome.[7]

| Type I | Type II | Type III | |

|---|---|---|---|

| J wave amplitude | >= 2mm | >= 2mm | >= 2mm |

| T wave | Negative | Positive or biphasis | Positive |

| ST-T configuration | Coved type | Saddleback | Saddleback |

| ST segment (terminal portion) | Gradually descending | Elevated >= 1mm | Elevated < 1mm |

- Examples of Brugada syndrome type I

- Examples of Brugada syndrome type II

External links

- Cardiogenetics website of the AMC cardiogentica.nl

- Brugada.org

- Genereview Brugada

- Brugada drugs contains lists of medications that should be avoided in patients with Brugada syndrome and medication that can be used to diagnose the syndrome

References

Error fetching PMID 1309182:

Error fetching PMID 13104407:

Error fetching PMID 11772879:

Error fetching PMID 12776858:

Error fetching PMID 11901046:

Error fetching PMID 12417552:

Error fetching PMID 18838563:

Error fetching PMID 15642768:

- Error fetching PMID 1309182:

- Error fetching PMID 11772879:

- Error fetching PMID 12776858:

- Error fetching PMID 11901046:

- Error fetching PMID 15642768:

- Error fetching PMID 15898165:

- Error fetching PMID 18838563:

- Error fetching PMID 12417552:

- Error fetching PMID 13104407: