Syncope: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

''Auteur: Louise R.A. Olde Nordkamp'' | |||

''Supervisor: Wouter Wieling'' | |||

==Definition== | |||

Syncope is a transient loss of consciousness (TLOC) due to global cerebral hypoperfusion characterized by rapid onset, short duration and spontaneous complete recovery. This excludes other causes of TLOC such as neurological, psychological and metabolic causes. | Syncope is a transient loss of consciousness (TLOC) due to global cerebral hypoperfusion characterized by rapid onset, short duration and spontaneous complete recovery. This excludes other causes of TLOC such as neurological, psychological and metabolic causes. | ||

{| class="wikitable" width="250px" | |||

|- | |||

! colspan="2" | Causes of (non-traumantic) transient loss of consciousness: | |||

|- | |||

|colspan="2" | 1. Syncope | |||

|- | |||

| || a. Reflex syncope | |||

|- | |||

| || b. Orthostatic hypotension | |||

|- | |||

| || c. Cardiac syncope | |||

|- | |||

|colspan="2" | 2. Neurological disorders | |||

|- | |||

|colspan="2" | 3. Psychiatrical disorders | |||

|- | |||

|colspan="2" | 4. Metabolic disorders | |||

|} | |||

==Classification Of Syncope== | ==Classification Of Syncope== | ||

Revision as of 03:00, 25 March 2013

Auteur: Louise R.A. Olde Nordkamp

Supervisor: Wouter Wieling

Definition

Syncope is a transient loss of consciousness (TLOC) due to global cerebral hypoperfusion characterized by rapid onset, short duration and spontaneous complete recovery. This excludes other causes of TLOC such as neurological, psychological and metabolic causes.

| Causes of (non-traumantic) transient loss of consciousness: | |

|---|---|

| 1. Syncope | |

| a. Reflex syncope | |

| b. Orthostatic hypotension | |

| c. Cardiac syncope | |

| 2. Neurological disorders | |

| 3. Psychiatrical disorders | |

| 4. Metabolic disorders | |

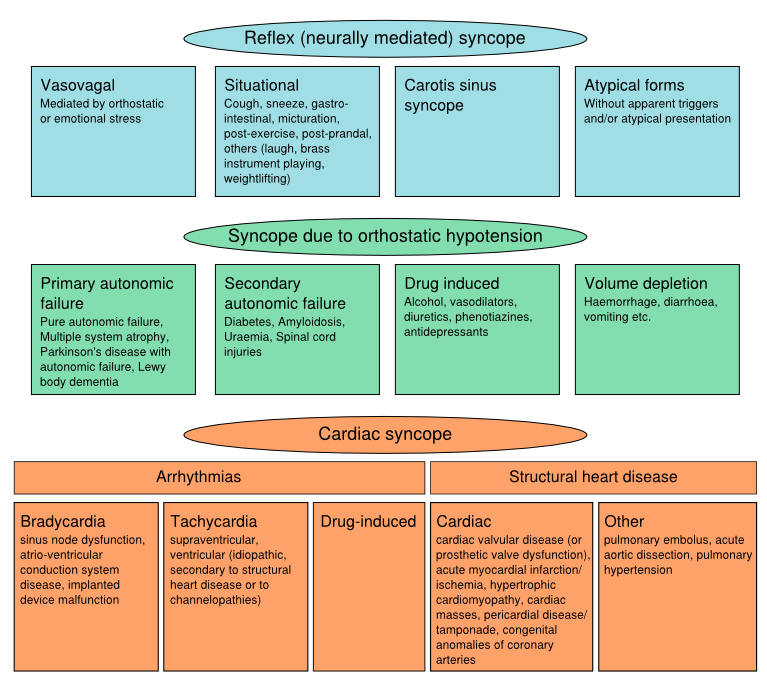

Classification Of Syncope

Pathophysiology

Syncope can be caused by a low peripheral resistance (vasodepressor type), a low cardiac output (cardioinhibitory type) or a combination of both.

A low peripheral resistance can be caused by an inappropriate reflex, or autonomic failure. A low cardiac output can be caused by reflex bradycardia, arrhythmias, or structural cardiac diseases or inadequate venous return.

Epidemiology

Syncope is common in the general population. The life-time cumulative incidence of ≥1 syncopal episodes in teenagers in the general population is high, with about 40 % by the age of 21 years. Reflex syncope is by far the most common cause. The majority have experienced reflex-mediated syncope episodes as teenagers and adolescents. The frequency of orhtostatic hypotension and cardiac syncope increases with age. Approximately 10-30% of the syncope episodes in patients above 60 years visiting a hospital for their syncope episodes are of cardiac origin.

Clinical features

History taking is the most important feature in syncope evaluation. After that the following clinical features are suggestive of a specific cause of syncope:

| Reflex (neurally mediated) syncope |

|

| Syncope due to orthostatic hypotension |

|

| Cardiac syncope |

|

In all patients presenting to a physician with syncope an ECG is recommended to screen for a cardiac cause of syncope. Holter monitoring is indicated only in patients who have very frequent syncopes or presyncope. In-hospital monitoring (in bed or telemetric) is warranted only when the patient has important structural heart disease and is at high risk of life-threatening arrhythmias.

When the mechanism of syncope remains unclear after full evaluation, an implantable loop recorder is indicated in patients who have clinical or ECG features suggesting arrhythmic syncope.

Reflex syncope

Diagnostic evaluation

Reflex syncope refers to a heterogeneous group of conditions in which there is a relatively sudden change in autonomic nervous system activity (decreased sympathic tonus causing less vasoconstriction and increased parasympathic (vagal) tonus causing bradycardia), triggered by a central (e.g. emotions, pain, blood phobia) or peripheral (e.g. prolonged orthostasis or increased carotid sinus afferent activity). It leads to a fall in blood pressure and cerebral perfusion. The range of bradycardia varies widely in reflex syncope, from a small reduction in peak heart rate to several seconds of asystole. As reflex syncope requires a reversal of the normal autonomic outflow, it usually occurs in people with a functional autonomic nervous system and should therefore be distinguished from syncope due to neurogenic orthostatic hypotension in patients with chronic autonomic failure.

Adequate history taking reveals the clinical features associated with a syncopal event that are important to differentiate the different causes of syncope. Vasovagal syncope, a specific form of reflex syncope, is diagnosed if syncope is precipitated by emotional distress or orthostatic stress and is associated with typical prodromes (such as nausea, warmth, pallor, light-headedness, and/or diaphoresis).

Head-up-tilt testing is used to examine the susceptibility to reflex syncope in patients who present with syncope of unknown cause. During head-up-tilt-testing a patient is passively changed from supine to upright position using a tilt-table.

Treatment

The prognosis of reflex syncope is excellent. However, syncope episodes can have a considerable impact on quality of life, because of its unexpected nature and fear for recurrences. Initial treatment of reflex syncope consists of non-pharmacological treatment measures, including reassurance regarding the benign nature of the condition, increasing the dietary salt and fluid intake, moderate exercise training, and physical counterpressure maneuvres (muscle tensing).

Orthostatic hypotension

Diagnostic evaluation

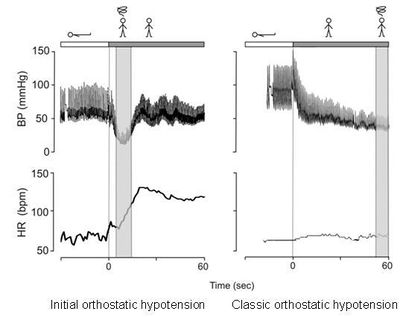

Orthostatic hypotension can be divided into three variants depending on the time interval between rising from supine position to complaints of light-headedness and/or fainting.

Initial orthostatic hypotension is defined as a transient blood pressure decrease (>40 mmHg systolic blood pressure (BP) and/or >20 mmHg diastolic BP) within 15 seconds of standing. It can only be present during active standing, because the initial drop in BP is not seen during head-up-tilt test in which both BP and heart rate (HR) gradually increases until stabilization is reached. Because of the rapid initial changes, it can only be detected by continuous beat-to-beat BP measuring of finger arterial.

Classical orthostatic hypotension is defined as a sustained reduction of systolic blood pressure of at least 20 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure of 10 mmHg within 3 min of standing or head-up tilt to at least 60 degree on a tilt table. Because the fall of BP is dependent on the baseline BP, a reduction in systolic BP of 30 mmHg may be a more appropriate criterion for OH in patients with supine hypertension. Orthostatic hypotension is a clinical sign and may be symptomatic or asymptomatic and can be a result of primary or secondary autonomic failure. Classical orthostatic hypotension can be detected during bedside evaluation with an active lying-to-standing test using the manual cuff.

Delayed orthostatic hypotension is a sustained reduction of systolic BP beyond 3 minutes of standing. These delayed falls in BP may be a mild or early form of sympathetic adrenergic failure. It can be detected with an extended lying-to-standing test or during head-up-tilt test.

Treatment

Initial treatment is educating regarding awareness and possible avoidance of triggers (e.g. hot crowded environments, volume depletion), early recognition of premonitory symptoms and performing manoeuvres to abort the episode (e.g. supine posture, muscle tensing). Drug-induced autonomic failure is probably the most frequent cause of orthostatic hypotension; in these cases elimination of the offending agents, mainly diuretics and vasodilators, is the main strategy. Alcohol is also commonly associated with orthostatic intolerance. Additionally, in some patients expanding intravascular volume by encouraging a higher than normal salt- and fluid intake can be helpful.

Cardiac syncope

Diagnostic evaluation

Cardiac arrhythmias, both brady- and tachyarrhythmias can cause syncope, due to a decrease in cardiac output. Additional factors which determine the susceptibility to syncope due to arrhythmias are the type of arrhythmia (atrial or ventricular), the status of left ventricular function, posture and the adequacy of vascular compensation are important. Structural heart disease can cause syncope when circulatory demands outweigh the impaired ability of the heart rate to increase its output.

Higher age, an abnormal ECG (rhythm abnormalities, conduction disorders, hypertrophy, old myocardial infarction, possible acute ischaemia, and AV block), a history of cardiovascular disease, especially ventricular arrhythmia, heart failure, syncope occurring without prodrome or during effort or supine, were found to be predictors of arrhythmia and/or 1-year mortality.

If cardiac syncope is suspected cardiac evaluation (echocardiography, stress testing, electrophysiological study, and prolonged ECG monitoring including loop recorder) is recommended.

Treatment

Syncope due to documented cardiac arrhythmias must receive treatment appropriate to the cause in all patients. Cardiac pacing, ICDs, and catheter ablation are the usual treatments of syncope due to cardiac arrhythmias, depending on the mechanism of syncope. For structural heart diseases treatment is best directed at amelioration of the specific structural lesion or its consequences.

References

- The ESC Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. Second edition. Editors: Camm AJ, Luscher TF, Serruys PW. 2009. Oxford university press.

- Freeman R et al. Consensus statement on the definition of orthostatic hypotension, neurally mediated syncope and the postural tachycardia syndrome. Clin Auton Res 2011; 21:69-72

- Hainsworth R. Pathophysiology of syncope. Clin Auton Res 2004; 14: Suppl 1:18-24

- Moya A et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope. Eur Heart J 2009; 30:2631-71

- Wieling W et al. Symptoms and signs of syncope: a review of the link between physiology and clinical clues. Brain 2009; 132:2630-42.