Chronic Coronary Disease: Difference between revisions

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

== Screening == | == Screening == | ||

Because extensive coronary disease can exist with minimal or no symptoms, screening for coronary disease has been suggested. Although screening results in indentifying patients at increased risk there is lack of evidence that screening actually improves outcome. <Cite>REFNAME5</Cite> | Because extensive coronary disease can exist with minimal or no symptoms, screening for coronary disease has been suggested. Although screening results in indentifying patients at increased risk there is lack of evidence that screening actually improves outcome. <Cite>REFNAME5</Cite> | ||

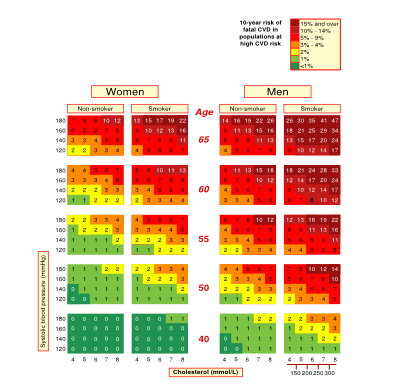

[[File:Mortality_risk_for_people_with_heart_disease_and_type_2_diabetes.svg | [[File:Mortality_risk_for_people_with_heart_disease_and_type_2_diabetes.svg|400px]] | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

Revision as of 21:47, 21 January 2012

Even though chronic coronary disease mortality rates have declined since 1970 it is still the leading cause of death in many western countries and in an increasing number of non western countries. [1]

The cause of the reduction in mortality rates is mainly due to rapid recognition at special cardiac care units and the possibility of early intervention. [2], [3]

But because survivors of a myocardial infarction still face a substantial risk of further cardiovascular events recognizing and reducing of risk factors is very important.

Risk Factors

The following risk factors for chronic coronary disease are modifiable and should be tackled. [4]

Cigarette Smoking

Cigarette smoking damages the endothelium of the blood vessels potentially facilitating cholesterol adherence. Smoking is a reversible and therefore a leading preventable cause of coronary disease. All patients who smoke should be counselled to give up smoking. Nicotine replacement therapy and behavioural therapy can assist . [ OR 2.87 for current vs never, PAR 35.7% for current and former vs never.]

Hypertension

Hypertension is defined as a systolic pressure >140 mmHg and/or diastolic pressure >90 mmHg. Patients with hypertension should be first treated with non pharmacologic therapies, including salt restriction, weight reduction in overweight/obese patients, and avoidance of excess alcohol intake. Antihypertensive drugs are indicated in patients with persistent hypertension despite non pharmacologic therapy. Most patients will require multiple antihypertensive drug therapies. [ OR 1.91, PAR 17.9%]

Cholesterol

Cholesterol is the felon in the atherosclerosis tale and therefore cholesterol levels in the blood should be optimal, meaning low LDL levels and high HDL levels. This can be achieved by the use of lipid lowering therapy which include statins. [ OR 3.25 for top vs lowest quintile, PAR 49.2% for top four quintiles vs lowest quintile]

Obesity

Obesity is associated with several risk factors for coronary heart disease, including hypertension, high cholesterol and insulin resistance as well as diabetes. Data show a relationship of higher body weight with morbidity and mortality from coronary disease. All patients who are willing, ready and able to lose weight should receive information about behaviour modification, diet, and increased physical activity. [OR 1.12 for top vs lowest tertile and 1.62 for middle vs lowest tertile, PAR 20.1% for top two tertiles vs lowest tertile]

Prevention

Exercise

Exercise lowers morbidity and mortality from coronary disease. [ OR 0.86, PAR 12.2%]

Healthy Diet

A healthy diet potentially results in a lower risk of coronary disease. A healthy diet consists of high intake of fruit and vegetables, high fiber intake, a low glycemic index and load, unsaturated fat rather than saturated fat, a limited intake of red or processed meat and intake of omega 3 fatty acids. [OR 0.70, PAR 13.7% for lack of daily consumption of fruits and vegetables]

Several studies have shown that people who have a high intake of fruit and vegetables have reduced risk coronary disease. It is possible that this is due to specific compounds in vegetables and fruits, or because people who eat more vegetables and fruits tend to eat less meat and saturated fat.

In diabetes mellitus tight glycemic control is important to protect against many vascular complications, including coronary disease. [OR 2.37, PAR 9.9%]

A small amount of alcohol results in a lower risk of morbidity and mortality from coronary disease. [OR 0.91, PAR 6.7%]

Screening

Because extensive coronary disease can exist with minimal or no symptoms, screening for coronary disease has been suggested. Although screening results in indentifying patients at increased risk there is lack of evidence that screening actually improves outcome. [5]

References

- Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, Carnethon M, Dai S, De Simone G, Ferguson TB, Ford E, Furie K, Gillespie C, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Hailpern S, Ho PM, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lackland D, Lisabeth L, Marelli A, McDermott MM, Meigs J, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino M, Nichol G, Roger VL, Rosamond W, Sacco R, Sorlie P, Stafford R, Thom T, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Wong ND, Wylie-Rosett J, and American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Executive summary: heart disease and stroke statistics--2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010 Feb 23;121(7):948-54. DOI:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192666 |

- Capewell S, Beaglehole R, Seddon M, and McMurray J. Explanation for the decline in coronary heart disease mortality rates in Auckland, New Zealand, between 1982 and 1993. Circulation. 2000 Sep 26;102(13):1511-6. DOI:10.1161/01.cir.102.13.1511 |

- Heidenreich PA and McClellan M. Trends in treatment and outcomes for acute myocardial infarction: 1975-1995. Am J Med. 2001 Feb 15;110(3):165-74. DOI:10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00712-9 |

- Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, McQueen M, Budaj A, Pais P, Varigos J, Lisheng L, and INTERHEART Study Investigators. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004 Sep 11-17;364(9438):937-52. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9 |

- Gibbons RJ, Balady GJ, Bricker JT, Chaitman BR, Fletcher GF, Froelicher VF, Mark DB, McCallister BD, Mooss AN, O'Reilly MG, Winters WL, Gibbons RJ, Antman EM, Alpert JS, Faxon DP, Fuster V, Gregoratos G, Hiratzka LF, Jacobs AK, Russell RO, Smith SC, and American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Committee to Update the 1997 Exercise Testing Guidelines. ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for exercise testing: summary article. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Update the 1997 Exercise Testing Guidelines). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002 Oct 16;40(8):1531-40. DOI:10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02164-2 |