Myocardial Infarction: Difference between revisions

| (4 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:MyocardialInfarction.svg|thumb|right|400px|Myocardial Infarction]] | |||

An acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is most commonly caused by rupture or erosion of an atherosclerotic plaque with superimposed thrombus formation. The underlying process is atherosclerosis, a chronic disease in which artery walls thicken by deposition of fatty materials such as cholesterol and inflammatory cells. The accumulation of this material results in the formation of an atherosclerotic plaque, encapsulated by connective tissue, which can narrow the lumen of the arteries significantly and progressively causing symptoms as angina pectoris or lead to an ACS. Depending on the presence of myocardial damage and typical ECG characteristics, ACS can be divided into ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), and non-ST-segment ACS including non-ST-segment elevation MI (NSTEMI) and unstable angina. In the case of STEMI and NSTEMI, there is biochemical evidence of myocardial damage (infarction). <Cite>REFNAME1</Cite> | |||

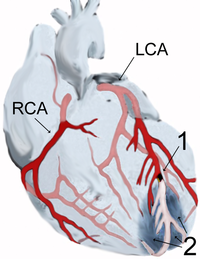

[[File:AMI_scheme.png|thumb|right|200px|A myocardial infarction results from a coronary occlusion (1) with necrosis of myocardial tissue (2) distal to the occlusion]] | [[File:AMI_scheme.png|thumb|right|200px|A myocardial infarction results from a coronary occlusion (1) with necrosis of myocardial tissue (2) distal to the occlusion]] | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

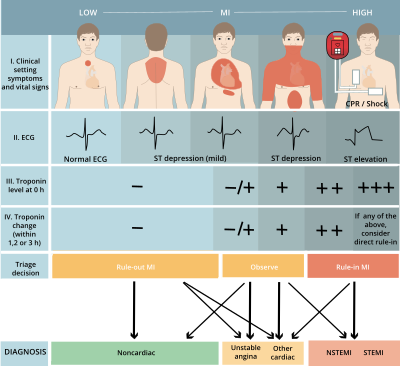

[[File: | [[File:chest_pain_to_NSTEMI_STEMI_v2.svg|thumb|400px|right|Different terminology is used during different phases of the chest pain workup. The ECG classifies into ST elevtion or not. Troponine definitely classifies into myocardial infarction (damage) or not.]] | ||

The most typical characteristic of an ACS is acute prolonged chest pain. <Cite>REFNAME2</Cite> The pain does not decrease at rest and is only temporarily relieved with nitroglycerin. Frequent accompanying symptoms include a radiating pain to shoulder, arm, back and/or jaw. <Cite>REFNAME3</Cite> Shortness of breath can occur, as well as sweating, fainting, nausea and vomiting, so called vegetative symptoms. Some patients including elderly and diabetics may present with aspecific symptoms. <Cite>REFNAME4</Cite>, <Cite>REFNAME5</Cite> | The most typical characteristic of an ACS is acute prolonged chest pain. <Cite>REFNAME2</Cite> The pain does not decrease at rest and is only temporarily relieved with nitroglycerin. Frequent accompanying symptoms include a radiating pain to shoulder, arm, back and/or jaw. <Cite>REFNAME3</Cite> Shortness of breath can occur, as well as sweating, fainting, nausea and vomiting, so called vegetative symptoms. Some patients including elderly and diabetics may present with aspecific symptoms. <Cite>REFNAME4</Cite>, <Cite>REFNAME5</Cite> | ||

| Line 64: | Line 65: | ||

===Non-ST-segment elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome=== | ===Non-ST-segment elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome=== | ||

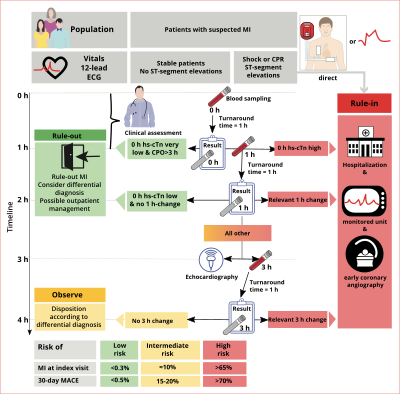

[[Image:Non-ST-segment elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome.svg|thumb|right|400px]] | |||

[[Image:Non-ST-segment elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome2.svg|thumb|right|400px]] | |||

[[Image:Swe.jpg|thumb|right|400px|link=http://www.outcomes-umassmed.org/grace/acs_risk/acs_risk_content.html|The [http://www.outcomes-umassmed.org/grace/acs_risk/acs_risk_content.html GRACE risk score model]]] | [[Image:Swe.jpg|thumb|right|400px|link=http://www.outcomes-umassmed.org/grace/acs_risk/acs_risk_content.html|The [http://www.outcomes-umassmed.org/grace/acs_risk/acs_risk_content.html GRACE risk score model]]] | ||

Comparable to STEMI, revascularization in NSTE-ACS relieves symptoms, shortens hospital | Comparable to STEMI, revascularization in NSTE-ACS relieves symptoms, shortens hospital | ||

Latest revision as of 07:53, 2 March 2021

An acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is most commonly caused by rupture or erosion of an atherosclerotic plaque with superimposed thrombus formation. The underlying process is atherosclerosis, a chronic disease in which artery walls thicken by deposition of fatty materials such as cholesterol and inflammatory cells. The accumulation of this material results in the formation of an atherosclerotic plaque, encapsulated by connective tissue, which can narrow the lumen of the arteries significantly and progressively causing symptoms as angina pectoris or lead to an ACS. Depending on the presence of myocardial damage and typical ECG characteristics, ACS can be divided into ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), and non-ST-segment ACS including non-ST-segment elevation MI (NSTEMI) and unstable angina. In the case of STEMI and NSTEMI, there is biochemical evidence of myocardial damage (infarction). [1]

History

The most typical characteristic of an ACS is acute prolonged chest pain. [2] The pain does not decrease at rest and is only temporarily relieved with nitroglycerin. Frequent accompanying symptoms include a radiating pain to shoulder, arm, back and/or jaw. [3] Shortness of breath can occur, as well as sweating, fainting, nausea and vomiting, so called vegetative symptoms. Some patients including elderly and diabetics may present with aspecific symptoms. [4], [5]

It is important to complete the medical history (prior history of ischemic events or vascular disease), risk factors for cardiovascular disease (a.o. diabetes mellitus, current smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia) and family history (first degree relatives with myocardial infarction before the age 55 of (males) or 65 (females) and/or sudden cardiac death). [6]

Symptoms of heart failure such as orthopnea (dyspnoea when lying flat), progressive dyspnoea and peripheral oedema are indicative of the extent of the problem. [7]

Physical Examination

The focus of the physical examination should be to recognize signs of systemic hypoperfusion such as hypotension, tachycardia, impaired cognition, pale and ashen skin. [7]

Furthermore, signs of heart failure are important, such as pulmonary crackles during auscultation and pitting oedema of the ankles.

In more stable ACS patients, history and physical examination are helpful to exclude other causes of chest pain, such as aortic valve stenosis, aorta dissection, arrhythmias, pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, heartburn, hyperventilation or musculoskeletal problems. [7]

Electrocardiogram (ECG)

An electrocardiogram (ECG) should be made on arrival in every patient with suspected ACS. [7]

The ECG is an important and easy modality which can assist in the diagnosis and prognostication of ACS. However, a single ECG may not reflect the dynamic pathophysiology of the ACS. Therefore it is important to make serial ECGs, certainly if a patient has ongoing symptoms. [7]

Furthermore, the ECG is also helpful in localising the ischemia:

- Anterior wall ischemia - One or more of leads V2-V5

- Anteroseptal ischemia - Leads V1 to V3

- Apical or lateral ischemia - Leads aVL and I, and leads V4 to V6

- Inferior wall ischemia - Leads II, III, and aVF

- Posterior wall – Leads V7-V9

- Right ventricle – Leads V3R, V4R, V1

- Left main coronary artery ischemia – Lead aVR

More information abou the ECG during myocardial infarction can be found on ECGpedia.

Cardiac Markers

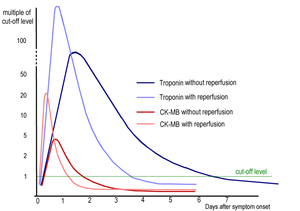

Cardiac markers are essential in order to confirm the diagnosis of MI, indicated by elevated Creatine Kinase isoenzyme MB (CK MB) and/or (high-sensitive) troponins. Troponins are more specific and sensitive than CK MB. The cardiac troponin concentration begins to rise around 4 hours after the onset of myocardial cell damage.[8]

With high-sensitive troponins, myocardial cell damage can be detected even earlier. It can take 4-6 hours before the CK MB concentration is elevated. Serial measurements are useful in order to estimate infarct size and increase the sensitivity of the (older) assays. [9]

A pitfall concerning mildly elevated cardiac markers can be patients with renal failure or pulmonary embolism. [10]

Treatment

As the formation of an intracoronary thrombus is a central mechanism in ACS and (recurrent) subsequent outcomes, the cornerstone in the treatment of ACS is antithrombotic treatment. All patients diagnosed with ACS should start with aspirin and a P2Y12 receptor blocker (clopidogrel, prasugrel or ticagrelor). [11] Aspirin and the P2Y12 receptor blocker are both platelet aggregation inhibitors. The treatment of ACS also focuses on medication to reduce the workload of the heart. ß blockers lower heart rate and blood pressure, to decrease the oxygen demand of the heart. [12] Nitrates dilatate the coronary arteries. [13]

Depending on the (working) diagnosis STEMI or NSTE-ACS, the revascularisation strategy varies.

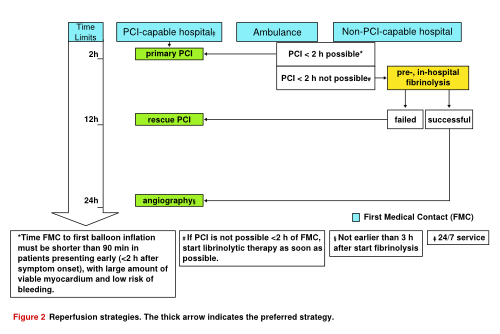

ST-segment elevation Myocardial Infarction

Initial treatment of STEMI is relief of ischemic pain, stabilisation of hemodynamic status and restoration of coronary flow and myocardial tissue perfusion. Reperfusion therapy should be initiated as quickly as possible by preferably primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or fibrinolysis. Reperfusion is beneficial up to 12 hours after the onset of symptoms. In case of severe hemodynamic compromise, reperfusion therapy may be attempted up to 24 hours after symptom onset. Meanwhile other measures as continuous ECG monitoring, oxygen supply and intravenous access are indicated. [7]

Primary PCI is the preferred revascularisation method for patients with STEMI. It is an effective method of securing and maintaining coronary patency and avoids the higher bleeding risk associated with fibrinolysis. If a patient is referred to a non-PCI-capable hospital, and transfer to a PCI-capable hospital in order to perform PCI within 2 hours after the onset of symptoms is not possible, fibrinolytic therapy is recommended.

There are circumstances in which transfer to a PCI qualified hospital is recommended:

- Patients with contraindications for fibrinolysis, such as: active bleedings, recent surgery, past history of intracranial bleeding. [14]

- Patients with cardiogenic shock, severe heart failure and/or pulmonary oedema complicating the myocardial infarction. [15], [16]

Available data support the pre-hospital initiation of fibrinolytics if this reperfusion strategy is indicated. Fibrinolytics like streptokinase and rtPA stimulate the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin. Plasmin degrades fibrin which is an important constituent of the thrombus. Fibrinolytics are most effective the first hours after the onset of symptoms, and a benefit is observed in terms of reducing mortality within the first twelve hours. [17] The hazards of thrombolysis are increased bleeding risk, including hemorrhagic strokes. Because re occlusion after fibrinolysis is possible patients should be transferred if possible to a PCI qualified hospital once fibrinolysis is done. [18]

In rare cases, CABG is indicated, such as failed fibrinolysis with coronary anatomy unsuited for PCI and/or failed PCI, when the patient develops cardiogenic shock, life threatening ventricular arrhythmias, has three vessel disease, or mechanical complications of the MI. [19]

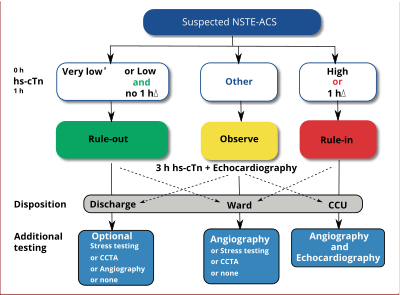

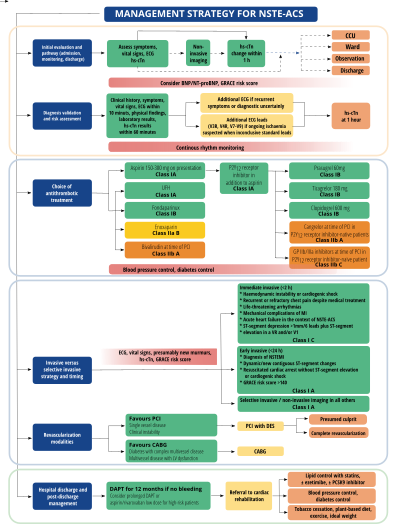

Non-ST-segment elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome

Comparable to STEMI, revascularization in NSTE-ACS relieves symptoms, shortens hospital stay, and improves prognosis. However, NSTE-ACS patients represent a heterogenous population, and indication and timing of revascularization depend on many factors, including the baseline risk of the patient. According to current guidelines, depending on early risk stratification a choice has to be made between a routine invasive or a selective invasive (or “conservative strategy”) [20]

Early risk stratification is helpful to identify patients at high risk who might benefit the most from a more aggressive therapeutic approach in order to prevent further ischemic events. [21]

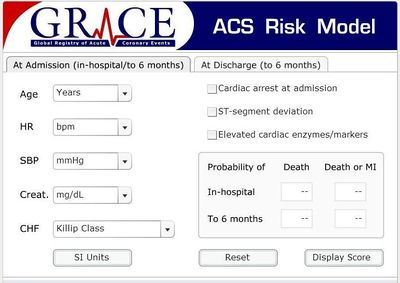

| GRACE risk score | ||||

| Risk Category | low | Intermediate | High | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSTEMI Probability of Death In-hospital (%) | <1 | 1-3 | >3 | |

| NSTEMI 6 Month Post-discharge Mortality | <3 | 3-8 | >8 | |

| STEMI In-hospital Mortality (%) | <2 | 2-5 | >5 | |

| STEMI 6 Month Post-discharge Mortality | <4.4 | 4.5-11 | >11 | |

Early risk stratification can be performed using one of the validated risk scores, such as the GRACE risk score. GRACE calculates the probability of death while in hospital. The following characteristics are taken into account:

- Age

- Heart rate and systolic BP

- Creatinine

- Killip class

- Cardiac arrest at admission

- Elevated cardiac markers

- ST segment deviation

Regarding treatment strategies in NSTE-ACS, many randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses have assessed the effects of a routine invasive vs. conservative or selective invasive approach in the short and long term. Recent meta-analyse suggest a benefit of the routine invasive management that is mainly visible in intermediate- to high-risk patients. (referentie)

Selective invasive (“or conservative”) management

Patients undergoing a selective invasive (“or conservative”) management are initially stabilized by medication only, including aspirin and clopidogrel orally and nitro-glycerin, heparin and a beta blocker intravenously. If the patients is unstable or has refractory angina, he/she is referred for coronary angiography. Patients stabilized on medical therapy should undergo a stress test before discharge. Potential advantages of this treatment strategy are a reduction of the number of catherization procedures. A potential disadvantage is a prolonged stay in the hospital. Although meta-analyses suggest the superiority of a routine invasive management, trials in which the selective invasive strategy was characterized by high rates of revascularization show equivalence of the two strategies.

Routine invasive management

The routine invasive strategy consists of routine, early coronary angiography within 24 hours after admission and subsequent revascularization if appropriate by PCI or CABG based on the angiographic findings. The optimal timing of coronary angiography with an intended routine invasive management is debated. In patients with high risk features, including hypotension, ventricular arrhythmias or a large myocardial area at risk, should undergo urgent angiography (<2 hours).

Cardiac rehabilitation

Cardiac rehabilitation reduces mortality, helps the patient to regain confidence and to resocialise, and helps to reduce risk factors for atherosclerosis. Post-ACS patient should be referred for cardiac rehabilitation.

References

- Davies MJ. Pathophysiology of acute coronary syndromes. Indian Heart J. 2000 Jul-Aug;52(4):473-9.

- Swap CJ and Nagurney JT. Value and limitations of chest pain history in the evaluation of patients with suspected acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2005 Nov 23;294(20):2623-9. DOI:10.1001/jama.294.20.2623 |

- Foreman RD. Mechanisms of cardiac pain. Annu Rev Physiol. 1999;61:143-67. DOI:10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.143 |

- Canto JG, Shlipak MG, Rogers WJ, Malmgren JA, Frederick PD, Lambrew CT, Ornato JP, Barron HV, and Kiefe CI. Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and mortality among patients with myocardial infarction presenting without chest pain. JAMA. 2000 Jun 28;283(24):3223-9. DOI:10.1001/jama.283.24.3223 |

- Pope JH, Ruthazer R, Beshansky JR, Griffith JL, and Selker HP. Clinical Features of Emergency Department Patients Presenting with Symptoms Suggestive of Acute Cardiac Ischemia: A Multicenter Study. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 1998 Jul;6(1):63-74. DOI:10.1023/A:1008876322599 |

- Lloyd-Jones DM, Nam BH, D'Agostino RB Sr, Levy D, Murabito JM, Wang TJ, Wilson PW, and O'Donnell CJ. Parental cardiovascular disease as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease in middle-aged adults: a prospective study of parents and offspring. JAMA. 2004 May 12;291(18):2204-11. DOI:10.1001/jama.291.18.2204 |

- Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, Bates ER, Green LA, Hand M, Hochman JS, Krumholz HM, Kushner FG, Lamas GA, Mullany CJ, Ornato JP, Pearle DL, Sloan MA, Smith SC Jr, Alpert JS, Anderson JL, Faxon DP, Fuster V, Gibbons RJ, Gregoratos G, Halperin JL, Hiratzka LF, Hunt SA, Jacobs AK, and American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction). ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction--executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction). Circulation. 2004 Aug 3;110(5):588-636. DOI:10.1161/01.CIR.0000134791.68010.FA |

- Macrae AR, Kavsak PA, Lustig V, Bhargava R, Vandersluis R, Palomaki GE, Yerna MJ, and Jaffe AS. Assessing the requirement for the 6-hour interval between specimens in the American Heart Association Classification of Myocardial Infarction in Epidemiology and Clinical Research Studies. Clin Chem. 2006 May;52(5):812-8. DOI:10.1373/clinchem.2005.059550 |

- Puleo PR, Meyer D, Wathen C, Tawa CB, Wheeler S, Hamburg RJ, Ali N, Obermueller SD, Triana JF, and Zimmerman JL. Use of a rapid assay of subforms of creatine kinase MB to diagnose or rule out acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1994 Sep 1;331(9):561-6. DOI:10.1056/NEJM199409013310901 |

- Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction, Jaffe AS, Apple FS, Galvani M, Katus HA, Newby LK, Ravkilde J, Chaitman B, Clemmensen PM, Dellborg M, Hod H, Porela P, Underwood R, Bax JJ, Beller GA, Bonow R, Van der Wall EE, Bassand JP, Wijns W, Ferguson TB, Steg PG, Uretsky BF, Williams DO, Armstrong PW, Antman EM, Fox KA, Hamm CW, Ohman EM, Simoons ML, Poole-Wilson PA, Gurfinkel EP, Lopez-Sendon JL, Pais P, Mendis S, Zhu JR, Wallentin LC, Fernández-Avilés F, Fox KM, Parkhomenko AN, Priori SG, Tendera M, Voipio-Pulkki LM, Vahanian A, Camm AJ, De Caterina R, Dean V, Dickstein K, Filippatos G, Funck-Brentano C, Hellemans I, Kristensen SD, McGregor K, Sechtem U, Silber S, Tendera M, Widimsky P, Zamorano JL, Morais J, Brener S, Harrington R, Morrow D, Lim M, Martinez-Rios MA, Steinhubl S, Levine GN, Gibler WB, Goff D, Tubaro M, Dudek D, and Al-Attar N. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007 Nov 27;116(22):2634-53. DOI:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187397 |

- Hamm CW, Bassand JP, Agewall S, Bax J, Boersma E, Bueno H, Caso P, Dudek D, Gielen S, Huber K, Ohman M, Petrie MC, Sonntag F, Uva MS, Storey RF, Wijns W, Zahger D, and ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2011 Dec;32(23):2999-3054. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehr236 |

- Fox K, Garcia MA, Ardissino D, Buszman P, Camici PG, Crea F, Daly C, De Backer G, Hjemdahl P, Lopez-Sendon J, Marco J, Morais J, Pepper J, Sechtem U, Simoons M, Thygesen K, Priori SG, Blanc JJ, Budaj A, Camm J, Dean V, Deckers J, Dickstein K, Lekakis J, McGregor K, Metra M, Morais J, Osterspey A, Tamargo J, Zamorano JL, Task Force on the Management of Stable Angina Pectoris of the European Society of Cardiology, and ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG). Guidelines on the management of stable angina pectoris: executive summary: The Task Force on the Management of Stable Angina Pectoris of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2006 Jun;27(11):1341-81. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehl001 |

- Abrams J. Hemodynamic effects of nitroglycerin and long-acting nitrates. Am Heart J. 1985 Jul;110(1 Pt 2):216-24.

- Grzybowski M, Clements EA, Parsons L, Welch R, Tintinalli AT, Ross MA, and Zalenski RJ. Mortality benefit of immediate revascularization of acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in patients with contraindications to thrombolytic therapy: a propensity analysis. JAMA. 2003 Oct 8;290(14):1891-8. DOI:10.1001/jama.290.14.1891 |

- Thune JJ, Hoefsten DE, Lindholm MG, Mortensen LS, Andersen HR, Nielsen TT, Kober L, Kelbaek H, and Danish Multicenter Randomized Study on Fibrinolytic Therapy Versus Acute Coronary Angioplasty in Acute Myocardial Infarction (DANAMI)-2 Investigators. Simple risk stratification at admission to identify patients with reduced mortality from primary angioplasty. Circulation. 2005 Sep 27;112(13):2017-21. DOI:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.558676 |

- Kent DM, Schmid CH, Lau J, and Selker HP. Is primary angioplasty for some as good as primary angioplasty for all?. J Gen Intern Med. 2002 Dec;17(12):887-94. DOI:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.11232.x |

- Bassand JP, Danchin N, Filippatos G, Gitt A, Hamm C, Silber S, Tubaro M, and Weidinger F. Implementation of reperfusion therapy in acute myocardial infarction. A policy statement from the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2005 Dec;26(24):2733-41. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehi673 |

- Silber S, Albertsson P, Avilés FF, Camici PG, Colombo A, Hamm C, Jørgensen E, Marco J, Nordrehaug JE, Ruzyllo W, Urban P, Stone GW, Wijns W, and Task Force for Percutaneous Coronary Interventions of the European Society of Cardiology. Guidelines for percutaneous coronary interventions. The Task Force for Percutaneous Coronary Interventions of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2005 Apr;26(8):804-47. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehi138 |

- Canadian Cardiovascular Society, American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, Antman EM, Hand M, Armstrong PW, Bates ER, Green LA, Halasyamani LK, Hochman JS, Krumholz HM, Lamas GA, Mullany CJ, Pearle DL, Sloan MA, Smith SC Jr, Anbe DT, Kushner FG, Ornato JP, Pearle DL, Sloan MA, Jacobs AK, Adams CD, Anderson JL, Buller CE, Creager MA, Ettinger SM, Halperin JL, Hunt SA, Lytle BW, Nishimura R, Page RL, Riegel B, Tarkington LG, and Yancy CW. 2007 focused update of the ACC/AHA 2004 guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008 Jan 15;51(2):210-47. DOI:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.001 |

- Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, Bates ER, Green LA, Hand M, Hochman JS, Krumholz HM, Kushner FG, Lamas GA, Mullany CJ, Ornato JP, Pearle DL, Sloan MA, Smith SC Jr, Alpert JS, Anderson JL, Faxon DP, Fuster V, Gibbons RJ, Gregoratos G, Halperin JL, Hiratzka LF, Hunt SA, Jacobs AK, and American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction). ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction--executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction). Circulation. 2004 Aug 3;110(5):588-636. DOI:10.1161/01.CIR.0000134791.68010.FA |

- Antman EM, Cohen M, Bernink PJ, McCabe CH, Horacek T, Papuchis G, Mautner B, Corbalan R, Radley D, and Braunwald E. The TIMI risk score for unstable angina/non-ST elevation MI: A method for prognostication and therapeutic decision making. JAMA. 2000 Aug 16;284(7):835-42. DOI:10.1001/jama.284.7.835 |

- Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, Bates ER, Green LA, Hand M, Hochman JS, Krumholz HM, Kushner FG, Lamas GA, Mullany CJ, Ornato JP, Pearle DL, Sloan MA, Smith SC Jr, Alpert JS, Anderson JL, Faxon DP, Fuster V, Gibbons RJ, Gregoratos G, Halperin JL, Hiratzka LF, Hunt SA, Jacobs AK, and American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction). ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction--executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction). Circulation. 2004 Aug 3;110(5):588-636. DOI:10.1161/01.CIR.0000134791.68010.FA |

- Anderson JL, Karagounis LA, and Califf RM. Metaanalysis of five reported studies on the relation of early coronary patency grades with mortality and outcomes after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1996 Jul 1;78(1):1-8. DOI:10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00217-2 |

- Bassand JP, Danchin N, Filippatos G, Gitt A, Hamm C, Silber S, Tubaro M, and Weidinger F. Implementation of reperfusion therapy in acute myocardial infarction. A policy statement from the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2005 Dec;26(24):2733-41. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehi673 |